BookNotes: Good Stocks Cheap by Kenneth Jeffrey Marshall

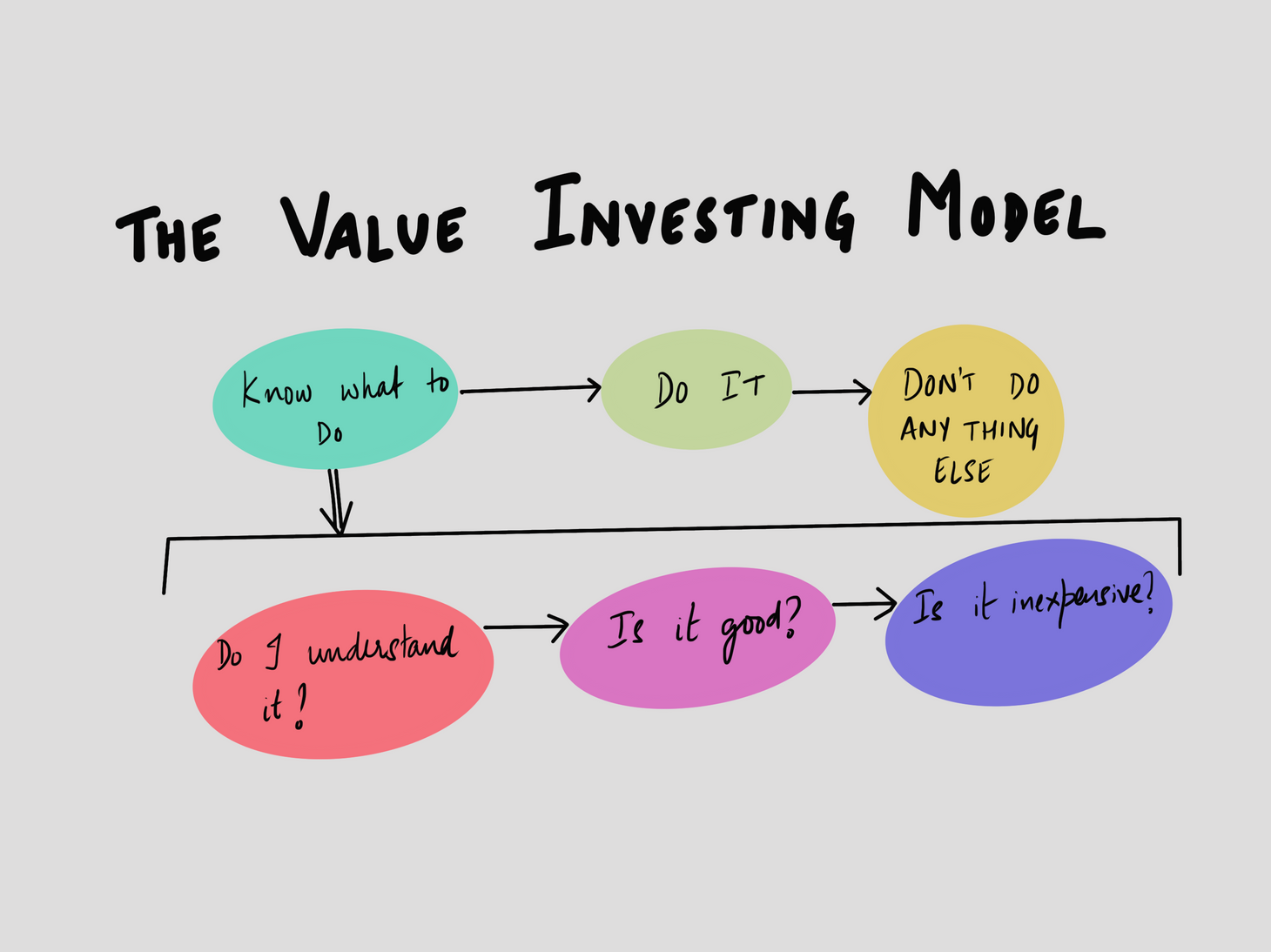

A manageable investing process.

Table of Contents

Hey there!

Last week’s article was a primer on derivatives. Though they’re considered complicated, derivatives are an integral part of the markets. So, if you missed it, check it out here.

But derivatives aren’t for everyone. In my opinion, only full time traders should trade derivatives. They, I would assume, constitute less than 1% of all market participants.

So today, let’s talk about a much loved asset class - equity. A lot of people are fascinated by equity. They’re awed by stories of Warren Buffett, and want their portfolios to do the exact same thing for them. They set out on that path, read 30 pages of the intelligent investor, and then, run out of steam. They get the philosophy, but crave to learn where to begin and where to end. Like Po when he wants to learn Kung Fu (in the movie Kung Fu Panda), they want to actually get kicking rather than keep learning the philosophy, discipline and breathing technique (though I’d be the first to admit that these are very important).

Which book helps an investor build a manageble investing process? It’s called Good Stocks Cheap, and is written by Kenneth Jeffrey Marshall. In less than 200 pages, Kenneth gives the reader a model to analyse companies, which he calls the Value Investing Model. This article summarises the model, and encourages serious investing enthusiasts to invest in his book.

Summary

The Value Investing Model breaks company analysis into three clearly defined steps:

- Do I understand it? ⇒ Defining the business along 6 parameters - products, customers, industry, form, geography, and status.

- Is it good? ⇒ Measuring past accounting performance. Articulating strategic positioning to gauge future performance. Assessing shareholder friendliness.

- Is it inexpensive? ⇒ Using both accounting data and market price to ascertain whether the business is worth buying at the current price. Since nothing is worth infinity.

The model is capped off by reiterating that investors aren't rewarded for activity, but only for being right. The three steps given above fall under the first two phases of the investment process - Phase one, know what to do; and phase two, do it. But phase 3 is the hardest one... do nothing else!

Detail

In every complex environment, an operating model is an opportunity to seize clarity. The value investing model achieves that. It's phases - know what to do, do it, and don’t do anything else - are behavioural. Functionally, an investor needs to follow the following three steps:

Step 1: Do I understand it?

Start off by defining the business in one clear, unambiguous sentence. The understanding statement. An understanding statement should focus on what a business is, and not what it could be. This is arrived at by clearly charting out:

- The products / services the company sells. Whether they are commodities or differentiated products.

- Who its customers are. You and I are users of Google search. But its customers are those who pay Google for advertising their brand to an audience (us).

- The industry in which it operates.

- Its legal and functional form. A legal form in India can be company, REIT, etc. and an example of functional form is franchisee (like Burger King India Limited).

- The geography in which its customers, operations, and headquarters are located.

- And finally, status is a residuary, blanket category in which stuff like - growing, fading, largest, etc. can be mentioned.

This step, once done well sets the investor up perfectly for the next one...

Step 2: Is it good?

This step is further divided into three sections:

1. Has it been good in the past?

This step involves the calculation of the following accounting ratios -

- return on capital employed,

- free cash flow return on capital employed,

- change in operating income per fully diluted share,

- change in free cash flow per fully diluted share,

- change in tangible book value per fully diluted share, and finally

- liabilities to equity.

These capture very well whether the business has been a good one in the past. It’s pertinent to bring in here, a quote from Warren Buffett, perhaps the greatest long term investor ever, which further validates Kenneth’s choice of accounting ratios:

“A good company is one that regularly makes a high return in cash terms on capital employed.”

2. Is it likely to be good in the future?

Kenneth believes, like I do, that in numerically estimating future revenues, costs, and profits of a business, we falsely mistake detail for precision. A better approach is to state with clarity, the strategic positioning of the business, and use that as a lens to gauge its future prospects. In the model, we do this on the following four fronts:

- Breadth analysis: Ask two questions. One, is the company’s customer base broad, and unlikely to consolidate? (The broader the customer base, the better. Since revenues don’t depend on one or a few large customers). And two, is the company’s supplier base broad and unlikely to consolidate? (Same logic as with customer base).

- Forces analysis: Here Kenneth uses four of Michael Porter’s five forces - bargaining power of customers, bargaining power of suppliers, threat of substitutes, and threat of new entrants. For each, the lower the better.

- Moat identification: A moat is simply something that helps the business stay profitable over a long period of time, despite the competition. Kenneth does a great job of explaining the various sources of a moat - government granted rights, network, cost advantage, brand value, high switching costs, and ingrainedness. (PS: Here, I’d written in detail about moats).

- And finally, taking a straightforward view on whether the market is growing - a simple yes or no.

3. Does the company have a history of being shareholder friendly?

The worst kind of company is one which grows a lot, but none of that growth flows to its owners. Because all of it is either eaten by the costs of the business, or by unscrupulous management. The aim of this section is to assess a possibility of the latter. It’s done on four fronts.

- By checking of unreasonable compensation to management, and whether the management themselves own any equity of the company. Management compensation should be appropriate to the size of the company and the country in which it operates.

- Check for shoddy related party transactions. Unless such transactions are made with utmost transparency and are clearly justified in the annual report, chances are, the company in question isn’t shareholder friendly.

- Check whether share buybacks have been done at unreasonably high prices. This usually indicates a willingness to appease the largest shareholders, which is undesirable. Also, it indicates a lack of opportunities in the business to use that cash for growth.

- And finally, dividends. Most investors love dividends. But high dividends could indicate a lack of avenues for growth in the business. And, the principal source of business growth, and consequently high investing returns, is the compounded returns earned on retained earnings.

It's important to note, that by ennumerating all the aspects above, one gets a well rounded view of what they're investing into.

After assessing whether the business has been good in the past, whether its likely to do well in future, and whether that prosperity is likely to flow to the shareholders, only one step remains...

Step 3: Is it inexpensive?

No matter how good a business is, the price we pay determines our future returns. For the astute investor, this step helps ascertain the timing of entering an investment. Here again, Kenneth uses four ratios:

- Market cap to free cash flow

- Enterprise price to operating income

- Market cap to book value

- Market cap to tangible book value

He further goes on to give levels for each ratio that he finds acceptable (which are, less than 8, 7, 5 and 3, respectively). But in my opinion, each investor should define that for themselves considering their native currency’s inflation and term deposit rates.

Conclusion

Kenneth states that the model is a step by step process of arriving at an investing decision. The minute the model throws up deal breakers, he stops his analysis mid-way. On the topic of selling, he’s of the view that an investor should hold good companies forever; only change that stance when one’s analysis is proved wrong, or something about the business changes that makes it not as good an investment anymore. That in itself calls for constant monitoring of portfolio companies by keeping an eye on financial results.

For me, Kenneth’s model has been a blessing. It brought clarity to my rather haphazard and endless investing process. With time, I have added things to my to-do list while assessing a company. But Kenneth's model stays the skeleton of my process.

If Kenneth ever sees this article, I’d just want to say a heartfelt thank you! :)

If you've reached till here, you're the real MVP! Thanks for reading! :)

Stebi Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.